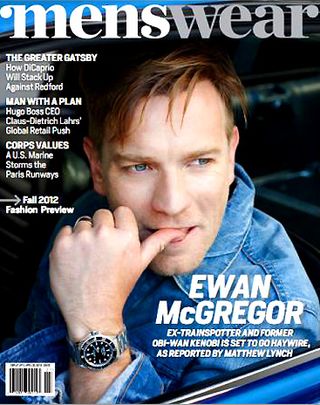

Ewan McGregor Is Ready to Rumble2012.02.20. 19:52, wwd.com

Menswear (2012.01.)

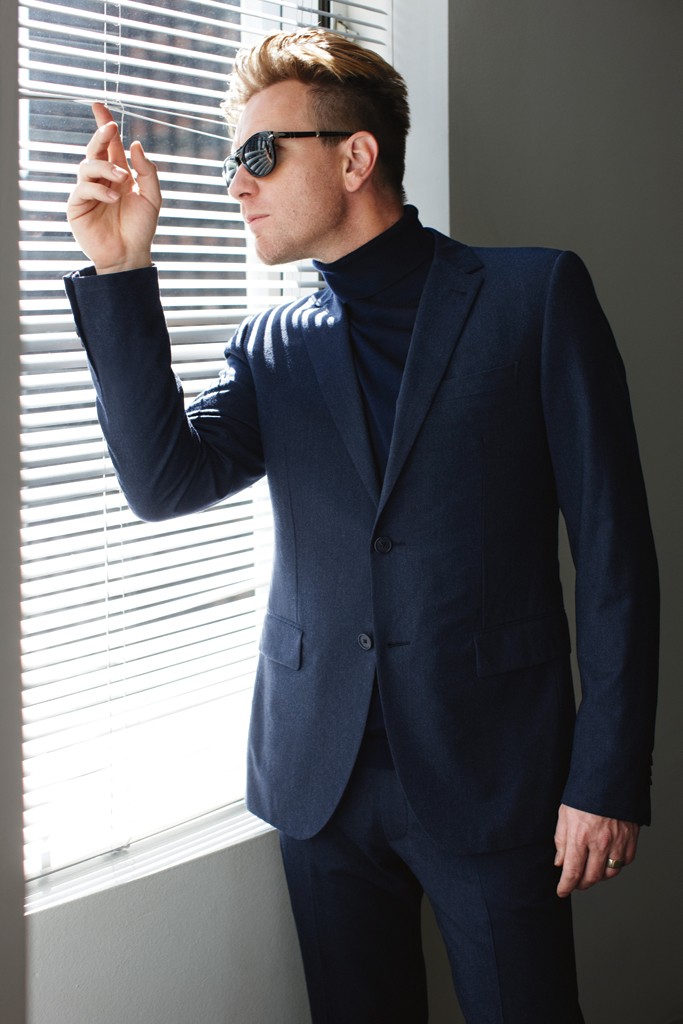

EWAN MCGREGOR IS BEAMING behind the wheel of his rusty 1960-something Volkswagen pickup in the parking lot of The Standard Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. A left and then a fewblocks and then one more left on South Main Street, and he’s at yet another parking lot, this one deserted for the day’s shoot. Still sporting the tailored navy suit and brown tie from the last few frames shot in the hotel, he’s quickly out of the battered VW and ogling one of the day’s props, the photographer’s midnight blue 1964 Mustang, the one with the tiny little side-view mirrors that look like they belong on a dentist’s tray, and the missing “D” on the hood that renders its make “FOR.” EWAN MCGREGOR IS BEAMING behind the wheel of his rusty 1960-something Volkswagen pickup in the parking lot of The Standard Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. A left and then a fewblocks and then one more left on South Main Street, and he’s at yet another parking lot, this one deserted for the day’s shoot. Still sporting the tailored navy suit and brown tie from the last few frames shot in the hotel, he’s quickly out of the battered VW and ogling one of the day’s props, the photographer’s midnight blue 1964 Mustang, the one with the tiny little side-view mirrors that look like they belong on a dentist’s tray, and the missing “D” on the hood that renders its make “FOR.”

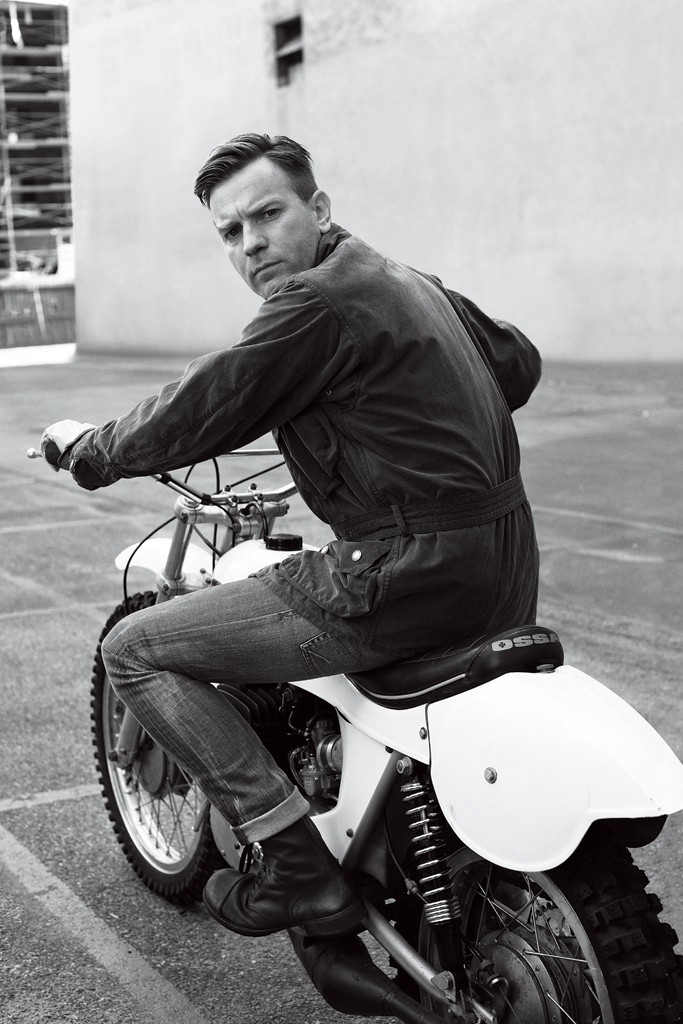

McGregor’s fondness for motor sports is well documented. A known gearhead, he has twice in the last decade embarked on cross-continental motorcycle trips — one around the northern hemisphere and one down the length of Africa. Both were broadcast as miniseries. On this day, he has his vintage Spanish test bike, another of the shoot’s props, lashed down in the bed of the pickup. He is still grinning when he takes the bike down the ramp, and later when a neighbor leans out a window to complain about its apparent lack of a muffler.

A day earlier, in the Spanish-style back patio of a Santa Monica café, no muscle cars or motorcycles or other toys in sight, that McGregor smile, the one he deploys with a glance to the middle distance when he makes sort of Zen pronouncements about his life or career, is on frequent display. Somewhere between content and amused, it is what a screenwriter might call a “knowing smile.”

It’s there when he offers, in his still-detectable Scottish lilt, his take on his family’s move three years ago to Los Angeles: “I always just assumed that I’d live in London forever. But I don’t, and I quite enjoy that.” Or his decision just more than a decade ago to quit drinking: “It was effortless, because it was the only thing I was prepared to give up. I wasn’t prepared to give up my career or my child — I wasn’t about to lose my children...11 years. Easy-peasy.” It’s there when he offers, in his still-detectable Scottish lilt, his take on his family’s move three years ago to Los Angeles: “I always just assumed that I’d live in London forever. But I don’t, and I quite enjoy that.” Or his decision just more than a decade ago to quit drinking: “It was effortless, because it was the only thing I was prepared to give up. I wasn’t prepared to give up my career or my child — I wasn’t about to lose my children...11 years. Easy-peasy.”

Or artifice in film, a favorite topic of disdain: “I hate scripts that read like other movies....That’s why I’ve never really nailed the Hollywood ‘hard man’ role, because I don’t really believe it. I don’t know guys who have great exit lines every time they leave the room.”

And later, in a discussion of his long résumé of sex scenes: “I love it when scriptwriters write, ‘They climax together,’ and I go, Oh yeah, really?” McGregor’s is the look of a man at total peace with how much he has figured out. And at 40 — more than half a decade removed from the Star Wars prequels and Moulin Rouge and that moment when there was a chance at all-out global megastardom — McGregor seems to have quite a bit figured out.

Yes, Ewan McGregor, who made his star turn 15 years ago as a nihilist junkie in Trainspotting, who always seemed willing to wear eyeliner and go full frontal, is 40. Though over tea, he doesn’t quite look it. Los Angeles has rendered his complexion a shade tanner than a son of Crieff, Scotland, should be capable of, and he’s dressed young: light-washed Levi’s, black leather Chuck Taylors and a black T-shirt with an elaborate Rorschach screen print. But when conversation turns to getting his teenage daughter to join the family for a shoot in London last summer, he doesn’t just sound middle-aged. He sounds like any other slightly harassed dad in the subdivision. Yes, Ewan McGregor, who made his star turn 15 years ago as a nihilist junkie in Trainspotting, who always seemed willing to wear eyeliner and go full frontal, is 40. Though over tea, he doesn’t quite look it. Los Angeles has rendered his complexion a shade tanner than a son of Crieff, Scotland, should be capable of, and he’s dressed young: light-washed Levi’s, black leather Chuck Taylors and a black T-shirt with an elaborate Rorschach screen print. But when conversation turns to getting his teenage daughter to join the family for a shoot in London last summer, he doesn’t just sound middle-aged. He sounds like any other slightly harassed dad in the subdivision.

“We can’t really drag her out of L.A. anymore, not with a team of wild horses,” he says with a laugh.

He’s been married to his wife, Eve, a production designer he met early in his career, for 16 years. The couple have four girls, ranging in age from 1 to 15. Over the years, he’s been largely guarded about his family life, but in conversation, he tends to define himself as much as a father as an actor.

“I’ve tried very hard to keep them out of the way, because it’s nothing to do with anybody, and it’s not fair on them,” he says. “We have a group of friends where some are in the business, some are not in the business — and all walks of the business: a lawyer, a writer, a director we know — and their kids and our kids are all friends. It’s not some kind of showbiz party around our house on the weekends. It’s far from it. It’s like real life.”

At times McGregor’s low-key cool and motorcycles and downright sane approach to the fame-family divide seem of another era. Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward and Westport come to mind.

Take, for example, an aside he offers about Haywire, which is in theaters Jan. 20 and is the ostensible reason for our sit-down. Helmed by Steven Soderbergh, the international spy thriller stars Gina Carano as an agent on the run, and McGregor as one of several GQ-ready spooks — played by Antonio Banderas, Michael Douglas, Michael Fassbender and Channing Tatum — who either employ or are out to extinguish her. Soderbergh, McGregor explains, put the cast at the preproduction mercy of a former Israeli special agent, who had them all packing fake blue .9 mm pistols to set the level of paranoia just right.

“I didn’t take my gun anywhere....I don’t want to be that guy who’s getting drawn on in the supermarket, when I’ve got my kids around, because I’ve got a rubber gun down the back of my pants,” he says, cracking up. “I kind of chickened out of it....Well, I got the point.” “I didn’t take my gun anywhere....I don’t want to be that guy who’s getting drawn on in the supermarket, when I’ve got my kids around, because I’ve got a rubber gun down the back of my pants,” he says, cracking up. “I kind of chickened out of it....Well, I got the point.”

Getting the point seems to be a McGregor specialty, and why not? He has been working for almost 20 years and has 50-something films to his credit. He is presumably set financially (though he refuses to take the bait when the subject of a back end on Obi-Wan Kenobi action figures is broached: “It wouldn’t be gentlemanly to talk about that”). He’s taken on a variety of work since, including a few that didn’t quite land as intended. If something less than megastardom followed that early-Naughts hot streak, McGregor seems perfectly at ease where he is now. He’s been on a bit of a new streak lately, which started in 2010 with Roman Polanski’s The Ghost Writer and continued last year with Mike Mills’ terrific Beginners, in which he played an angst-ridden, grief-stricken thirtysomething casting about Los Angeles with Mélanie Laurent and a Jack Russell terrier.

He has, in short, achieved the sort of work-life balance that would be maddening to the world at large if he didn’t tend to be such a goddamn nice guy about the whole thing. Unprompted, he twice rearranges the proceedings at the café to keep a very pale, very sweaty reporter out of the baking SoCal sun. He pitches the umbrella himself on the second go-round.

“[It’s] almost unnervingly natural, how relaxed he is,” says Carano. A mixed martial artist by training and a total acting novice before Haywire, she has a unique perspective on the matter.

“He’s so smart. Everyone else was so excited, and he’s just relaxed and cool and has all the smart, witty things to say, but he’s kind of quieter,” she says, recalling the cast’s first meeting in a hotel. “And then we all went downstairs and I see this guy take off on his motorcycle — the coolest, most antique motorcycle — and it was Ewan. I was like, ‘That’s Ewan McGregor.’ He’s just way too cool.”

Haywire and Beginners aside, McGregor is moving toward more familiar domestic territory on-screen these days. He’ll play, as he puts it, “a proper dad” in this year’s The Impossible, about a family upended by the tsunami in Thailand in 2004. Despite his being a father for nearly as long as he’s been working, it’s something of a first. Haywire and Beginners aside, McGregor is moving toward more familiar domestic territory on-screen these days. He’ll play, as he puts it, “a proper dad” in this year’s The Impossible, about a family upended by the tsunami in Thailand in 2004. Despite his being a father for nearly as long as he’s been working, it’s something of a first.

“It’s nice to feel like you’re working on grown-up films and playing a grown-up person,” he says of the development.

In March, he’s especially against type as a buttoned-up Scottish fisheries expert in Salmon Fishing in the Yemen. Lasse Hallström, the Swedish-born director of Chocolat and The Cider House Rules, who worked with McGregor on Salmon Fishing, cites the actor’s “sense of irony” as one of his greatest strengths. “Privately, he has a wonderful sense of humor,” the director says.

At the café, McGregor considers what’s left to accomplish. He says he’d like to direct, unaware of or, more likely, unbothered by the cliché. But acting, he says, is still an end itself.

“If every now and again one’s like a step out, that’s fine,” McGregor says of his role selection these days. “I’d like to feel I’m still climbing the ladder, if you like, but at the same time, it’s not the be-all and end-all. Because I’m really happy where I’m at.”

By now McGregor’s tea bag is on the glass tabletop, and the sun is starting to let up a little bit. It’s the time of day when, one imagines, the dutiful parents of the L.A. metro area line up their cars for the post-school pickup. Or maybe it’s the perfect hour or two to be on a bike, tooling around Southern California. Either way, our allotted time is drawing to a close and McGregor is soon back off to the real world.

But not without one last bit of insight.

“Your ambition,” he says with that smile, “can be to carry on doing what you’re doing.”

|